We recently attended two events organised by Bangladesh Garment Workers Solidarity (BGWS). One event commemorated a former colleague Aminul Islam Shama, former Organisational Secretary, Central Committee of Garment Sramik Samhati (GSS). The other was an essay writing competition for the children of garment workers.

At the latter event, the children were writing about their families and their lives – an entirely different kind of event to what we envision an event organised to counter backlash against labour rights would look like. On the surface, the connection between countering backlash and a children’s event seems tenuous. But, when you dig a little deeper, they are closely connected.

Struggle for a living wage

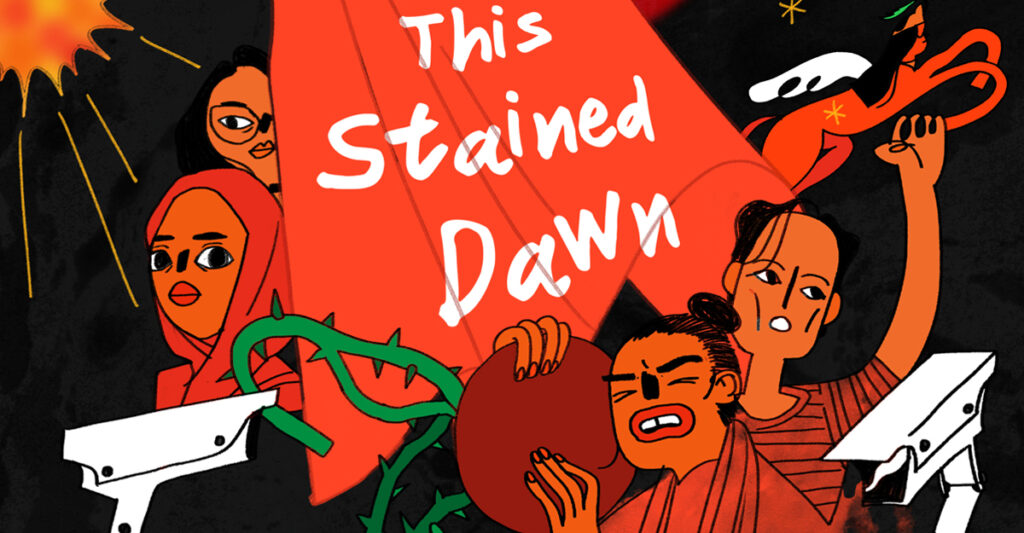

As part of our work to identify when, how, and why women’s struggles succeed in retaining power and sustaining gains against backlash, SuPWR in collaboration with BGWS are researching the movement for a living and fair wage in the ready-made garment (RMG) sector. RMG wages have not increased in the last three years and is due for a review. However, demands for fair and a living wage have met resistance. Labour rights activists have experienced various forms of repression, from verbal and physical abuse to cases being filed against them. At times, the activists have been labelled as ‘disruptors’ and ‘vandals’.

In 2023 the national election will be held, and the movement is gearing up to pressure the government and the opposition parties to listen to their demands. The increase in oil and gas prices and increased transportation costs have raised the prices of food and other essentials, making it difficult for RMG workers to meet the costs of children’s food and education. These concerns were repeatedly raised by various members of the struggle at the memorial event for Aminul Islam Shama.

Intergenerational impact of backlash

Our focus and analysis of backlash in SuPWR tends to be in the present. We focus on actions of the struggle members – what are the demands made, what kinds of reactions do these evoke, what are actions taken to counter the pushback. However, seeing first-hand the work BGWS is doing with the children of RMG workers reminded us that the temporal dimension of backlash involves exploring the intergenerational impact of backlash. The current resistance from employers and the state against the demands for a living wage has a direct impact on the nutritional, health, and educational attainment of the children. And the impact will only deepen in the long run as food and fuel prices continue to rise.

Children also witness the repressions faced by family members, which impacts them psychologically, creating feelings of insecurity and distrust in agencies that are supposed to secure workers’ and citizen’s rights.

The role of care in movements

BGWS’ work with children allows them to come together to play, use their creativity, and reflect on their experiences. It enables the children to cope with the difficulties they encounter, while at the same time enjoy their childhood. The children we met at both events were treated as if they belonged to all struggle members. The creation of this space for worker’s children by BGWS highlights the important role care plays in how labour rights organising takes place.

At the event, the discussion on the essays focused on how children viewed the sacrifices made by their parents to sustain the struggle for living wages. These sacrifices included giving up on spending quality family time or struggle member’s spouses working longer hours so they could devote more time to mobilising.

At the event, the discussion on the essays focused on how children viewed the sacrifices made by their parents to sustain the struggle for living wages. These sacrifices included giving up on spending quality family time or struggle member’s spouses working longer hours so they could devote more time to mobilising.

Workers require alternative spaces of care for their children that go beyond just ensuring physical safety. These alternative spaces stimulate children’s creativity and sense of self and enable them to go beyond the limitations of conventional curriculum taught in government schools. The struggle members view education provided in these alternative spaces as a pathway for a different and brighter future for their children.

Future leaders

The BGWS children’s space also creates scope for the older children to learn organisational speaking and other leadership skills. At the memorial event, the older children volunteered, and were effective organisers and speakers, with a clear sense of why the meeting was important. This was a training ground for future leaders to counter backlash against worker’s rights. These children will go on to ensure that the rights secured by their parent’s generation will not be eroded in whatever sectors and fields they enter in the future.