Online spaces, particularly social media, are central to the current feminist movement in Pakistan. There are valid criticisms about the limitations of employing online spaces for mobilisation in a country where internet connectivity is very low and the gender digital divide is one the highest in the world. Indeed, 11 October marks the International Day of the Girl Child, and the 2021 theme of “Digital generation. Our generation” aims to highlight and address this gender digital divide.

But while addressing the gender digital divide is crucial, we would argue that our collective digital responsibility to girls and women goes beyond this. In the last five years, online spaces have become central for the popularisation and organisation of urban-based feminist movements in Pakistan. It has also, unfortunately, become a source of vilification and backlash against them.

Early online backlash

In 2018, mainstream media (i.e., electronic and print) did not extensively cover the Aurat and Aurat Azadi marches. Calls to action, discourse, and backlash played out online. While organisers mobilised via social media, the backlash was swift and just as social media-savvy. So-called controversial posters containing slogans such as “mera jism meri marzi” (my body, my will) and “khud khana gharam karo” (heat your own food) initially only got attention online, and individual marchers were harassed with hate speech and misogynist comments through popular Facebook pages. Online disinformation was also used to attack overtly feminist causes, with Facebook pages photoshopping, often quite obviously so, placards.

Early anti-feminist organising online was not merely pockets of resistance, rather it was the groundwork for the backlash that followed. In 2019, the march grew substantially in terms of organising structure and numbers, soaring from a few hundred marchers to a few thousand. The backlash was swift and dramatic; applications for First Information Reports (FIRs) were filed in various police stations across the country on bad faith grounds, such as obscenity and immorality. Resolutions were moved in provincial assemblies calling for the march to be banned. In the eye of the storm were various placards being discussed on mainstream media, with organisers and feminists being asked to justify the usage of “controversial slogans” considered an existential threat to Pakistan’s culture.

Even after the second march, while primetime shows debated the appropriateness of slogans and tone-policed marchers, online spaces were ripe for more malicious threats against marchers and organisers. Twitter hashtags emerged as the primary site for anti-Aurat March propaganda – largely organised rather than organic – along with anti-feminist, pro-nationalist Facebook pages. YouTube was ripe with videos issuing death and rape threats against participants.

Dissecting the 2021 online disinformation campaign

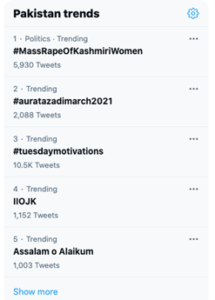

Things came to a head in 2021 when backlash resulted in immediate and grave threats for the organisers. In the lead-up to the march, several Twitter hashtags circulated – #ForeignFundedAuratMarch trended in Pakistan 7 March 2021 – and the march’s #AuratAzadiMarch2021 (trending on 23 February, 2021) was hijacked.

These attacks had now become synonymous with the march, but this time the disinformation took an unprecedented turn. A day before the march, threats directed towards organisers emerged in the form of videos by the Jamia Hafza in Islamabad, recalling the physical attacks the Aurat Aazadi March Islamabad faced in 2020.

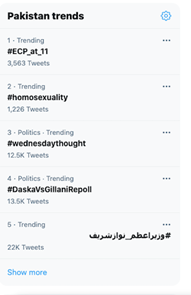

On March 9, 2021, three hashtags pertaining to the march sought to spread disinformation: #AuratMarchLhr_295c; #Anti_IslamAgenda; and #Homosexuality.

These hashtags referenced false accusations that the marches were anti-Islamic and blasphemous, with some referring to section 295-C of the Pakistan Penal Code, which carries a mandatory death sentence. This included:

- False allegations that the French flag was raised at the Aurat Azadi March in Islamabad (it was the flag of the Women Democratic Front, a left-wing feminist party). This was particularly dangerous because it came when the now-banned ultra-right-wing Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan were agitating for the expulsion of the French Ambassador for blasphemy-linked grievances.

- Malicious misinterpretation of Aurat March Lahore’s #MeToo blanket that bore testimonies of sexual abuse survivors. The accusation was subsequently debunked.

- A doctored video with superimposed slogans, which sought to give the impression that anti-Islamic slogans were raised at the march. journalists, influencers, and right-wing personalities amplified these accusations – trended through Twitter hashtags, propaganda-fuelled YouTube channels and videos, and Facebook pages – despite them being thoroughly fact-checked.

There were attempts to present counter-narratives through statements, fact-checks, and online campaigns. Hashtags such as #StopHateAgainstAuratMarch and #ApologisetoAuratMarch were used to demand accountability for disinformation campaigns. As online spaces became a battleground for the movement, a concerted online counter-narrative campaign was necessary for safety and survival.

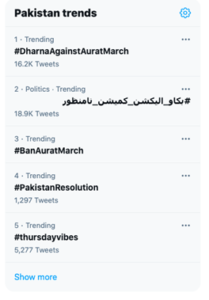

The sustained campaign of backlash ranged from inciting outright violence against marchers (#HangAuratMarchers) and banning the march (#BanAuratMarch) to numerous attempts to file FIRs for blasphemy against the organisers. Online disinformation became the default, due to years of relentless attacks with little or no counter-narrative from ruling governments and state institutions, and indifference from social media platforms.

Indifference of social media giants

Social media companies hold immense powers not only to decide what content is allowed on their platforms, but also to amplify content that generates maximum profits and views. Algorithmic-fuelled hate and misogyny is prevalent on all social media platforms, and the Aurat March has become fodder given its visible and viral nature. The pattern of Twitter hashtags described above highlights an acute power imbalance that cannot be course-corrected simply through counter-narratives in an environment where organisers are forced to deactivate accounts and are offered no protections by the state.

The march organisers identified hundreds of YouTube channels geared towards nationalist, Islamist, and misogynistic narratives that parroted disinformation against the march, viewed by thousands. Aurat March organisers brought the most flagrant videos to YouTube’s attention, however they were found not to violate its community guidelines. Twitter also failed to remove posts inciting violence against marchers (#HangAuratMarchers trended on Twitter on 12 March 2021). Preserving the right to free speech of these channels silence women and gender minorities in Pakistan, with no accounting for their right to expression online.

Conclusion

In light of the 2021 backlash, Aurat March organisers published a public statement calling out big tech companies for their failure to provide protections for gendered bodies on their platform. Feminist organisers in the Global South are stuck in a double-bind, reliant on masculinist, capitalist social media platforms to amplify their message, but at the same time endangered by them.

The ephemeral nature of social media might lull people into believing that its impact is fleeting. But disinformation online entrenches misogynistic narratives, diminishes the credibility of the feminist movement, and incites violence against organisers. It also raises questions about what organising means in online spaces, what feminist labour looks like in these spaces, and how to create counter-disinformation strategies while engaging in larger movement building.

To truly rise to the call of “Digital generation. Our generation”, we must ensure that girls and women don’t only have equal access to digital spaces, but that they are safe in these spaces.